Last year, as part of the Wonder of Will exhibition extravaganza to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, the Folger presented America’s Shakespeare. This exhibition took a look at the Bard’s influence on American thought and popular culture from the “Be taxt, or not be taxt” political cartoons at the dawn of the Revolution, to the countless reimaginings of Shakespeare’s works in recent literature and film. Who is Shakespeare to Americans, and how has the U.S. made Shakespeare our own?

One of the most striking stories involves a strange and eerie connection between Abraham Lincoln’s assassination and Shakespeare’s Macbeth. It’s not only a fascinating tale, but the digitized versions of original documents at the Folger and other U.S. institutions have provided a wonderful opportunity to show students how to tell a story using primary sources.

The three items in the exhibition that told our story were a letter written by Lincoln to his favorite actor, a broadside lamenting Lincoln’s death, and a page from Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth’s, diary. Macbeth is represented in each one of them.

Things to know going in:

- Abraham Lincoln was the President during the Civil War.

- Abraham Lincoln was assassinated at Ford’s Theatre on April 14th, 1865 by John Wilkes Booth, who saw Lincoln as a tyrant.

- Shakespeare was in the collective mind of the Nation. Abbreviated works appeared in school books and his poetry and plays were commonly taught, so the average American would have been familiar with his words.

Primary Source #1: Letter to James H. Hackett from Abraham Lincoln. August 17th, 1863. (Library of Congress)

In this letter, Lincoln writes to his favorite actor, James H. Hackett:

“Some of Shakespeare’s plays I have never read, while others I have gone over perhaps as frequently as any unprofessional reader. Among the latter are Lear, Richard Third, Henry Eighth, Hamlet, and especially Macbeth. I think nothing equals Macbeth—It is wonderful.”

Lincoln was known to keep a copy of Macbeth in his back pocket as he rode from town to town working as a young lawyer and was said to quote it frequently. Here, in this letter, he clearly identifies it as his favorite of all of Shakespeare’s plays—ask your students why that might be. (One possible take: a man who grew from a young farmer to the President of the United States might be able to connect with the play’s exploration of ambition, transformations, and power!)

SIDE NOTE: I know we are talking about Macbeth here, but take a look at the line right after:

“Unlike your gentlemen of the profession, I think the soliloquy in Hamlet commencing “O, my offense is rank” surpasses that commencing “To be, or not to be.”

It would be interesting to put the two Hamlet soliloquies side by side and compare them. Keep in mind that the Civil War was seen as a war between brothers, and Lincoln was tormented over it. A great, open-ended question for students: why might Lincoln prefer Claudius’ speech over one of the most famous speeches in all of literature?

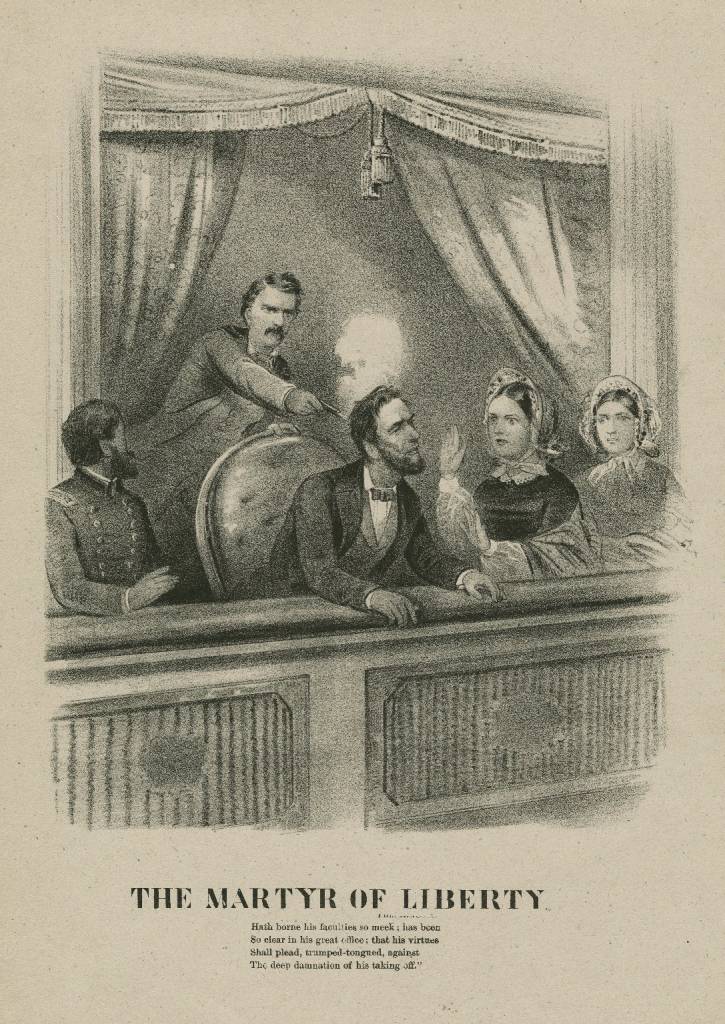

Primary Source # 2: “Martyr of Liberty” Broadside (Folger Shakespeare Library)

After Lincoln’s assassination, the nation fell into a deep mourning. Broadsides, such as this one, were a form of mass media in the 19th century and were similar to posters that could be hung in public spaces or sold and framed at home. This is one example of several broadsides that featured a dramatic image of Booth shooting Lincoln with a quote from Macbeth. This one in particular quotes Macbeth’s speech in Act 1, Scene 7, Lines 17-20:

“Hath borne his faculties so meek; has been

So clear in his great office; that his virtues

Shall plead, trumped-tongued, against

The deep damnation of his taking off.”

These lines are from a scene where Macbeth is lauding King Duncan, a man he plans to murder, for being so virtuous a ruler that his legacy would speak for him after death. The American public quickly made the connection between the two assassinations and used Shakespeare’s words to express their bereavement for their own leader who was unjustly struck down.

Primary Source #3: Page of John Wilkes Booth’s Diary (Ford’s Theatre)

After assassinating Lincoln, Booth was on the run for almost two weeks. Realizing that the authorities were closing in on him, he wrote his final diary entry on April 22nd, referencing Shakespeare twice.

He first cited Julius Caesar’s Brutus—another assassin—writing: “I am here in despair. And why; For doing what Brutus was honored for…”

He continues through his entry, recognizing that he is labeled a criminal and that his time is short. He ends his diary by quoting… you guessed it… Macbeth:

“but ‘I must fight the course.’ Tis all that’s left me.”

Booth was a well known Shakespearean actor like his brothers Edwin and Junius Brutus Jr. and his father Junius Brutus. He had played Macbeth in 1863, so he would have been intimately familiar with Macbeth’s words as he accepted his fate:

“They have tied me to a stake. I cannot fly,

But, bear-like, I must fight the course.”(Macbeth, Act 5, Scene 7, Lines 1-2)

And thereby hangs a tale of Lincoln and Macbeth.

At the Folger, we love telling people that we are “Shakespeare’s home in America.” Our location on Capitol Hill is no accident—our Founders, Henry and Emily Folger, saw the library as a gift to the American public and understood that Shakespeare was (and still is!) an integral part to telling the American story. Through these three primary sources, we can see Shakespeare’s works and words woven through a pivotal moment in American history.