By Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine

Editors of the Folger Shakespeare Library Editions

Love and marriage are the concerns of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew. The play offers us some strikingly different models of the process of attracting and choosing a mate and then coming to terms with the mate one has chosen. Some of these models may still seem attractive to us, some not. Lucentio’s courtship of and marriage to Bianca are prompted by his idealized love of an apparently ideal woman. When she first appears, Bianca is silent and perfectly obedient to her father. Lucentio then speaks of her as if she were a goddess come to earth. Because her father denies all men the opportunity openly to court Bianca, Lucentio spontaneously throws off his social status as a gentleman in order to disguise himself as a lowly tutor, the only kind of man that Bianca’s father, Baptista, will let near her. All that matters to Lucentio is winning Bianca’s heart. To marry her—even in secret and in shared defiance of her father—is surely, he believes, to be happy.

An alternative style of wooing adopted by Petruchio in quest of Katherine is notably free of idealism. Petruchio is concerned with money. He takes money from all Bianca’s suitors for wooing her older sister, Katherine, who, Baptista has dictated, must be married before Bianca. When Petruchio comes to see Katherine, he first arranges with her father the dowry to be acquired by marrying her. Assured of the money, Petruchio is ready to marry Katherine even against her will. Katherine is the shrew named in the play’s title; and, according to all the men but Petruchio, her bad temper denies her the status of “ideal woman” accorded Bianca by Lucentio. Yet by the end of the play, Katherine, whether she has been tamed or not, certainly acts much changed. Petruchio then claims to have the more successful marriage. But is the marriage of Petruchio and Katherine a superior match—have they truly learned to love each other?—or is it based on terror and deception?

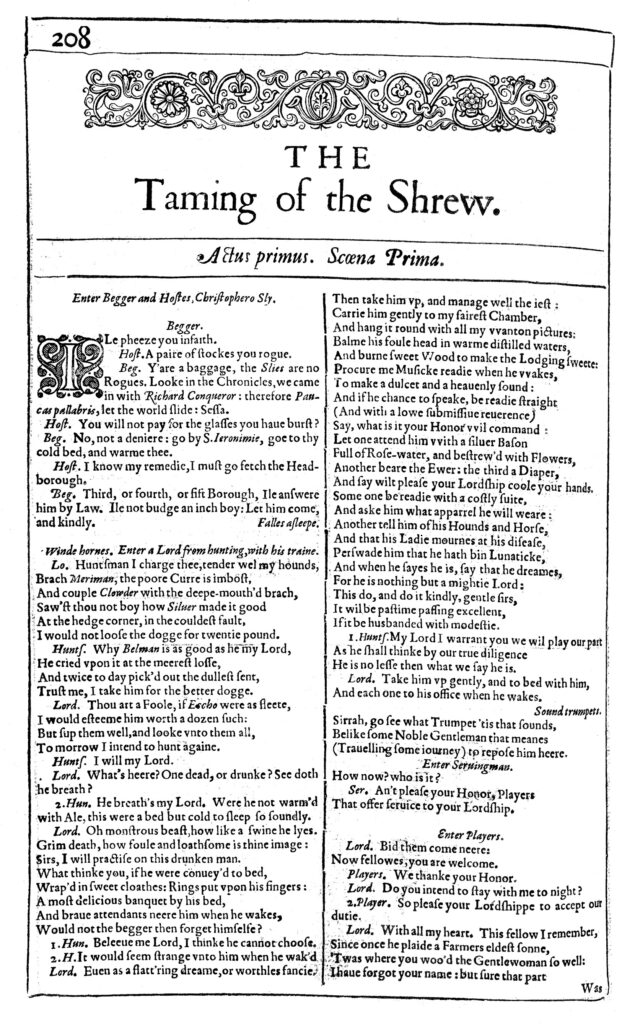

And what of the plot about Christopher Sly, the drunken tinker, with which the play opens, and which we, following editorial tradition, call “The Induction”? The play about Katherine, Petruchio, Bianca, and Bianca’s suitors actually begins as a comedy put on for the entertainment of the deceived Christopher Sly—that is, as a play-within-a-play. If we were to take Taming’s first two scenes as an opening frame within which the taming play is set, our questions about Katherine’s transformation or about Petruchio’s taming methods would perhaps need to be reformulated. If, that is, there existed a closing frame (as in other versions, in which the Sly figure watches the whole entertainment and learns from it how to tame his shrewish wife), we might respond to the play-within-the-play as a kind of parody on marriage customs and male fantasies about how women should and should not behave. Because The Taming of the Shrew exists in only one early printed form (the one in the 1623 First Folio), and because that printing lacks a closing frame for the Sly story, the opening Sly scenes are considered a prologue rather than part of a frame—though some productions borrow the closing frame from the anonymous Taming of a Shrew. (See Appendix, “Framing Dialogue in The Taming of a Shrew (1594).”) This basic question about how seriously we are to take its plots and characters may be the most intriguing question presented us by The Taming of the Shrew.

After you have read the play, we invite you to turn to “The Taming of the Shrew: A Modern Perspective,” by Professor Karen Newman of Brown University.

“. . . fair Padua, nursery of arts.” (1.1.2)

From Pietro Bertelli, Theatrum vrbium Italicarum . . . (1599).