By Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine

Editors of the Folger Shakespeare Library Editions

Henry IV, Part 1 was first printed in 1598 as a quarto. All that survives of that printing (known to scholars as Q0) is a single copy in the Folger Library of eight of its pages. These Q0 pages contain the lines numbered in the present edition as 1.3.206–2.2.117—lines which, in the present edition, are based directly on Q0. The rest of the present edition is based directly on the first printing of the play that survives in full.1 This is also a quarto (Q1), and it was also printed in 1598 by the same printer responsible for Q0, which appears to have served as printer’s copy for Q1. Henry IV, Part 1 was a popular book; it went through five more editions in quarto before its appearance in the First Folio of 1623. The Folio text was printed from a slightly edited copy of the Fifth Quarto of 1613 (Q5). Whoever prepared Q5 to be printer’s copy for the Folio restored some Q1 readings, but also introduced other changes, the authority for which is indeterminable. We have therefore not accepted these changes into the present edition.

Explore the last remaining fragment of the Q0 edition of Henry IV, part 1 (1598) in the Folger’s Digital Collections.

For the convenience of the reader, we have modernized the punctuation and the spelling of the quartos. Sometimes we go so far as to modernize certain old forms of words; for example, when a means “he,” we change it to he; we change mo to more and ye to you. But it has not been our editorial practice in any of the plays to modernize some words that sound distinctly different from modern forms. For example, when the early printed texts read sith or apricocks or porpentine, we have not modernized to since, apricots, porcupine. When the forms an, and, or and if appear instead of the modern form if, we have reduced and to an but have not changed any of these forms to their modern equivalent, if. We also modernize and, where necessary, correct passages in foreign languages, unless an error in the early printed text can be reasonably explained as a joke.

Whenever we change the wording of the quartos or add anything to their stage directions, we mark the change by enclosing it in superior half-brackets (⌜ ⌝). We want our readers to be immediately aware when we have intervened. (Only when we correct an obvious typographical error in the quartos does the change not get marked.) Whenever we change the quartos’ wording or change their punctuation so that meaning changes, we list the change in the textual notes, even if all we have done is fix an obvious error.

We, like a great many editors before us, regularize a number of the proper names. This issue is particularly vexed in Henry IV, Part 1 because the character Falstaff, as well as his companions Bardolph and Peto, appear occasionally in the earliest printed texts of both Henry IV, Part 1 and its sequel, Henry IV, Part 2, under quite different names. There is considerable evidence that Sir John Falstaff was originally called Sir John Oldcastle, the name of a fifteenth-century proto-Protestant martyr who was celebrated by sixteenth-century Protestant historians. In the First Quarto of Henry IV, Part 2, the speech prefix for one of Falstaff ’s speeches is “Old.,” and there survives in Henry IV, Part 1 what appears to be a joke on Falstaff ’s former name when Prince Hal addresses him as “my old lad of the castle” (1.2.44). According to a nearly contemporary report, Shakespeare and his acting company were obliged to abandon the name Oldcastle by the martyr’s descendant William Brooke, Lord Cobham, a powerful aristocrat who served as lord chamberlain to Elizabeth I in 1596–97. It is just possible that similar circumstances forced changes in the names of Peto and Bardolph, who are once referred to in the text of Henry IV, Part 1 as “Haruey and Rossill” (i.e., Harvey and Russell). Perhaps, the influential figures who bore those names in Shakespeare’s time objected, as Lord Cobham did, to having their ancestors put onstage.

Some editors have recently argued that the names Oldcastle, Harvey, and Russell should be substituted for Falstaff, Peto, and Bardolph so as to return the play to the form in which Shakespeare first wrote it. These editors assert that the only changes that were made to the play between the form in which it was originally staged and the form in which it has come down to us in print were the name changes. Against this view stands the fact that the only version of the play that has come down to us is the one in which the characters are named Falstaff, Peto, and Bardolph. Because we have only this version, it is impossible to know how it may differ from any other version, including the one in which the characters were named Oldcastle, Haruey, and Rossill. That is, to claim that Q1 is the original in all respects but in the name changes is to claim more than can be known. Our choice therefore is to print the names as they appear in the quartos, with the exception that, in 1.2, we regularize “Haruey” to “Peto,” and, in 1.2 and 2.4, we regularize “Rossill” and “Ross.” to “Bardolph.” We expand the often severely abbreviated forms of names used as speech headings in early printed texts into the full names of the characters. Variations in the speech headings of the early printed texts are recorded in the textual notes.

This edition differs from many earlier ones in its efforts to aid the reader in imagining the play as a performance rather than as a series of fictional events. For example, near the end of 3.3, Prince Hal tells Bardolph to “bear this letter to Lord John of Lancaster, . . . this to my Lord of Westmoreland” and, in the fiction of the play, gives Bardolph two letters. But in the staging of the play, one actor, in the role of Prince Hal, gives another, in the role of Bardolph, not some letters, but some papers representing letters. And so our stage direction reads “handing Bardolph papers” rather than “letters.” Whenever it is reasonably certain, in our view, that a speech is accompanied by a particular action, we provide a stage direction describing the action. (Occasional exceptions to this rule occur when the action is so obvious that to add a stage direction would insult the reader.) Stage directions for the entrance of characters in mid-scene are, with rare exceptions, placed so that they immediately precede the characters’ participation in the scene, even though these entrances may appear somewhat earlier in the early printed texts. Whenever we move a stage direction, we record this change in the textual notes. Latin stage directions (e.g., Exeunt) are translated into English (e.g., They exit).

In the present edition, as well, we mark with a dash any change of address within a speech, unless a stage direction intervenes. When the -ed ending of a word is to be pronounced, we mark it with an accent. Like editors for the past two centuries we display metrically linked lines in the following way:

We’ll fight with him tonight.

WORCESTER It may not be.

However, when there are a number of short verse lines that can be linked in more than one way, we do not, with rare exceptions, indent any of them.

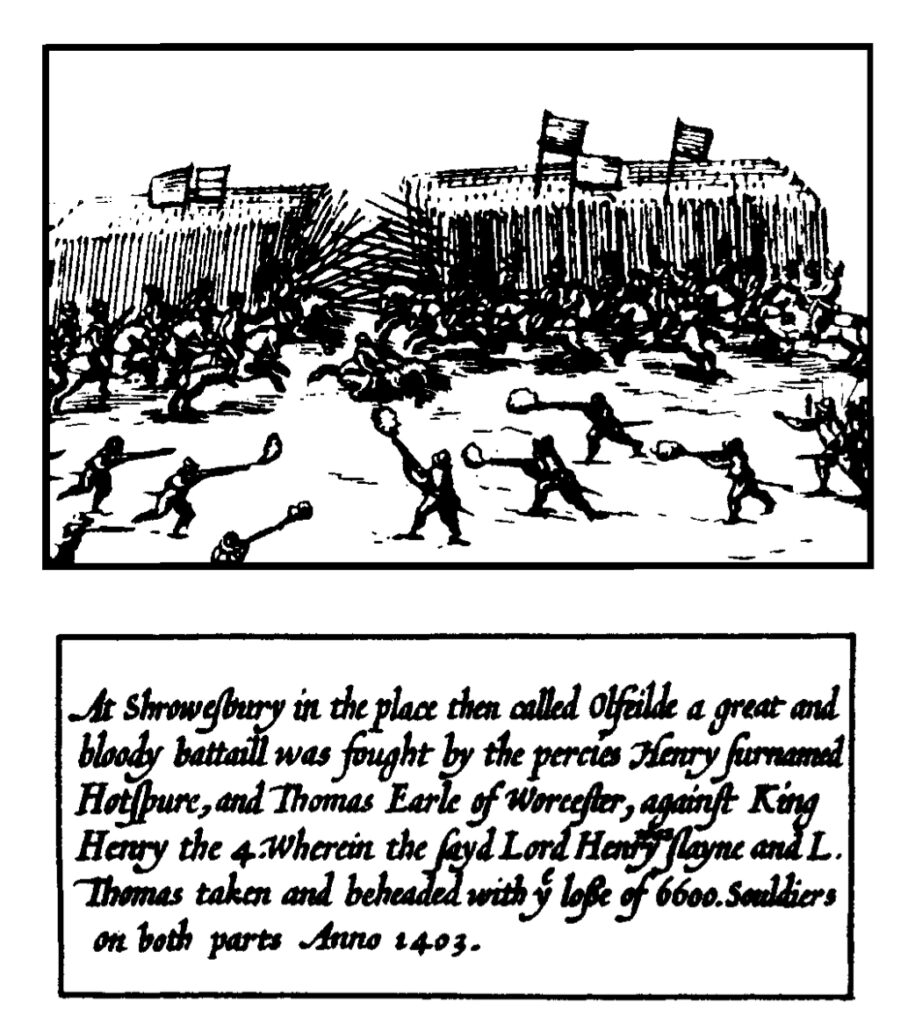

From John Speed, A prospect of the most famous part of the world (1631).